The unions want the Modi government to enact legislation conferring mandatory status to MSP, rather than just being an indicative or desired price.

Why are the unions seeking legal guarantee for MSP?

The Centre currently announces the MSPs of 23 crops. They include 7 cereals (paddy, wheat, maize, bajra, jowar, ragi and barley), 5 pulses (chana, tur/arhar, moong, urad and masur), 7 oilseeds (rapeseed-mustard, groundnut, soyabean, sunflower, sesamum, safflower and nigerseed) and 4 commercial crops (sugarcane, cotton, copra and raw jute). While the MSPs technically ensure a minimum 50% return on all cultivation costs, these are largely on paper. In most crops grown across much of India, the prices received by farmers, especially during harvest time, are well below the officially-declared MSPs. And since MSPs have no statutory backing, they cannot demand these as a matter of right. The unions want the Modi government to enact legislation conferring mandatory status to MSP, rather than just being an indicative or desired price.

How can that entitlement be implemented?

There are basically three ways.

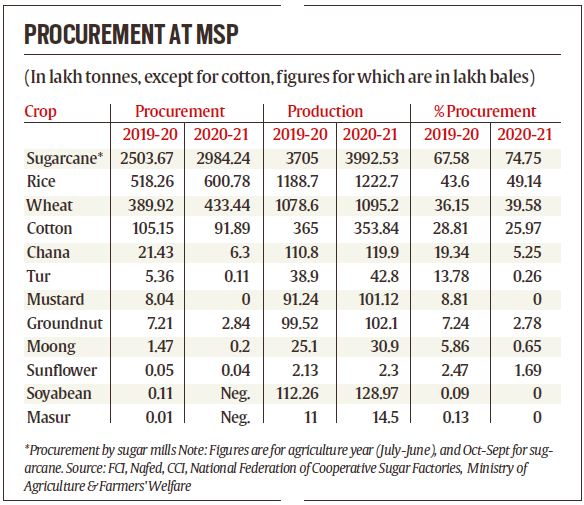

The first is by forcing private traders or processors to pay MSP. This is already applicable in sugarcane. Sugar mills are required, by law, to pay farmers the Centre’s “fair and remunerative price” for cane, with some state governments fixing even higher so-called “advised prices”. The Sugarcane (Control) Order, 1966 issued under the Essential Commodities Act, moreover, obliges payment of this legally-guaranteed price within 14 days of cane purchase. During the 2020-21 sugar year (October-September), mills crushed some 298 million tonnes (mt) of cane, which, the accompanying table shows, was close to three-fourths of the country’s estimated total production of 399 mt.

The second is by the government undertaking procurement at MSP through its agencies such as the Food Corporation of India (FCI), National Agricultural Cooperative Marketing Federation of India (Nafed) and Cotton Corporation of India (CCI). As can be seen from the table, such purchases accounted for nearly 50% of India’s rice/paddy production last year, while amounting to 40% for wheat and over 25% in cotton. Government agencies also bought significant quantities – upwards of 0.1 mt – of chana (chickpea), mustard, groundnut, tur (pigeon-pea) and moong (green gram) during 2019-20. Much of that was post the Covid-induced nationwide lockdown in April-June 2020, when the winter-spring rabi crops were being marketed by farmers. Procurement of these crops, however, fell in 2020-21. In the case of mustard, tur, moong, masur (yellow lentil) and soyabean, the need for procurement wasn’t really felt, as open market prices largely ruled above MSPs.

The second is by the government undertaking procurement at MSP through its agencies such as the Food Corporation of India (FCI), National Agricultural Cooperative Marketing Federation of India (Nafed) and Cotton Corporation of India (CCI). As can be seen from the table, such purchases accounted for nearly 50% of India’s rice/paddy production last year, while amounting to 40% for wheat and over 25% in cotton. Government agencies also bought significant quantities – upwards of 0.1 mt – of chana (chickpea), mustard, groundnut, tur (pigeon-pea) and moong (green gram) during 2019-20. Much of that was post the Covid-induced nationwide lockdown in April-June 2020, when the winter-spring rabi crops were being marketed by farmers. Procurement of these crops, however, fell in 2020-21. In the case of mustard, tur, moong, masur (yellow lentil) and soyabean, the need for procurement wasn’t really felt, as open market prices largely ruled above MSPs.

Generally speaking, MSP implementation has been effective only in four crops (sugarcane, paddy, wheat and cotton); partly so in five (chana, mustard, groundnut, tur and moong) and weak/non-existent in the remaining 14 notified crops. In livestock and horticultural produce – be it milk, eggs, onions, potatoes or apples – there is no MSP even on paper! The 23 MSP crops together, in turn, account for hardly a third of the total value of India’s agricultural output, excluding forestry and fishing.

The third route for guaranteeing MSP is via price deficiency payments. Under it, the government neither directly purchases nor forces the private industry to pay MSP. Instead, it allows all sales by farmers to take place at the prevailing market prices. Farmers are simply paid the difference between the government’s MSP and the average market price for the particular crop during the harvesting season.

What would be the fiscal cost of making the MSP legally binding?

The MSP value of the total output of all the 23 notified crops worked out to about Rs 11.9 lakh crore in 2020-21. But this entire produce wouldn’t have got marketed. The marketed surplus ratio – what remains after retention by farmers for self-consumption, seed and feeding of animals – is estimated to range from below 50% for ragi and 65-70% for bajra (pearl-millet) and jowar (sorghum), to 75-85% for wheat, paddy and sugarcane, 90%-plus for most pulses and 95-100% for cotton, soyabean, sunflower and jute. Taking an average of 75% yields a number – the MSP value of production actually sold by farmers – just under Rs 9 lakh crore.

The government is further, as it is, procuring many crops. The MSP value of the 89.42 mt of paddy and 43.34 mt of wheat alone bought during 2020-21 was around Rs 253,275 crore. To this, one must add the MSP value of pulses and oilseeds purchased by Nafed (Rs 21,901 crore in 2019-20 and Rs 4,948 crore in 2020-21) and kapas or raw un-ginned cotton by CCI (Rs 28,420 crore in 2019-20 and Rs 26,245 crore in 2020-21). Besides, the MSP value of the sugarcane crushed by mills (Rs 92,000 crore in 2020-21) has to be considered.

All in all, then, the MSP is already being enforced, directly or through fiat, on roughly Rs 3.8 lakh crore worth of produce. Providing legal guarantee for the entire marketable surplus of the 23 MSP crops would mean covering another Rs 5 lakh crore or so. It would be even lower, given two things. The crop that is bought by the government also gets sold, with the revenues from that partly offsetting the expenditures from MSP procurement. Secondly, government agencies needn’t buy every single grain coming in to the mandis. Mopping up even a quarter of market arrivals is often enough to lift prices above MSPs in most crops.

But there must be a catch to all these calculations?

Yes. FCI’s grain mountain is evidence of how cumbersome public procurement and stocking operations can be. This is not to mention the huge scope for corruption and recycling/leakage of wheat and rice, whether from godowns, ration shops or in transit. Also, while cereals and pulses can be sold through the public distribution system, disposal becomes complicated in the case of nigerseed, sesamum or safflower. Even when it comes to sugarcane, the experience of mills accumulating huge payment arrears to growers is proof of the practical limitations of “legal MSP”.

That leaves deficiency payments, which may be a more workable and fiscally feasible option in the long run. There is, in addition, a growing consensus among economists for guaranteeing minimum “incomes”, as against “prices”, to farmers. That would essentially entail making more direct cash transfers either on a flat per-acre (as in the Telangana government’s Rythu Bandhu scheme) or per-farm household (the Centre’s PM-Kisan) basis.

Written by Harish Damodaran

Source: Indian Express, 29/11/21