Helping the invisible hands of agriculture

With the ‘feminisation of agriculture’ picking up pace, the challenges women farmers face can no longer be ignored

October 15 is observed, respectively, as International Day of Rural Women by the United Nations, and National Women’s Farmer’s Day (Rashtriya Mahila Kisan Diwas) in India. In 2016, the Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers’ Welfare decided to take the lead in celebrating the event, duly recognising the multidimensional role of women at every stage in agriculture — from sowing to planting, drainage, irrigation, fertilizer, plant protection, harvesting, weeding, and storage.

This year, the Ministry has proposed deliberations to discuss the challenges that women farmers face in crop cultivation, animal husbandry, dairying and fisheries. The aim is to work towards an action plan using better access to credit, skill development and entrepreneurial opportunities.

Data and reality

Yet, paying lip service to them is not going to alleviate their drudgery and hardships in the fields. According to Oxfam India, women are responsible for about 60-80% of food and 90% of dairy production, respectively. The work by women farmers, in crop cultivation, livestock management or at home, often goes unnoticed. Attempts by the government to impart them training in poultry, apiculture and rural handicrafts is trivial given their large numbers. In order to sustain women’s interest in farming and also their uplift, there must be a vision backed by an appropriate policy and doable action plans.

The Agriculture Census (2010-11) shows that out of an estimated 118.7 million cultivators, 30.3% were females. Similarly, out of an estimated 144.3 million agricultural labourers, 42.6% were females. In terms of ownership of operational holdings, the latest Agriculture Census (2015-16) is startling. Out of a total 146 million operational holdings, the percentage share of female operational holders is 13.87% (20.25 million), a nearly one percentage increase over five years. While the “feminisation of agriculture” is taking place at a fast pace, the government has yet to gear up to address the challenges that women farmers and labourers face.

Issue of land ownership

The biggest challenge is the powerlessness of women in terms of claiming ownership of the land they have been cultivating. In Census 2015, almost 86% of women farmers are devoid of this property right in land perhaps on account of the patriarchal set up in our society. Notably, a lack of ownership of land does not allow women farmers to approach banks for institutional loans as banks usually consider land as collateral.

Research worldwide shows that women with access to secure land, formal credit and access to market have greater propensity in making investments in improving harvest, increasing productivity, and improving household food security and nutrition. Provision of credit without collateral under the micro-finance initiative of the National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development should be encouraged. Better access to credit, technology, and provision of entrepreneurship abilities will further boost women’s confidence and help them gain recognition as farmers. As of now, women farmers have hardly any representation in society and are nowhere discernible in farmers’ organisations or in occasional protests. They are the invisible workers without which the agricultural economy is hard to grow.

Second, land holdings have doubled over the years with the result that the average size of farms has shrunk. Therefore, a majority of farmers fall under the small and marginal category, having less than 2 ha of land — a category that, undisputedly, includes women farmers. A declining size of land holdings may act as a deterrent due to lower net returns earned and technology adoption. The possibility of collective farming can be encouraged to make women self-reliant. Training and skills imparted to women as has been done by some self-help groups and cooperative-based dairy activities (Saras in Rajasthan and Amul in Gujarat). These can be explored further through farmer producer organisations. Moreover, government flagship schemes such as the National Food Security Mission, Sub-mission on Seed and Planting Material and the Rashtriya Krishi Vikas Yojana must include women-centric strategies and dedicated expenditure.

Gender-friendly machinery

Third, female cultivators and labourers generally perform labour-intensive tasks (hoeing, grass cutting, weeding, picking, cotton stick collection, looking after livestock). In addition to working on the farm, they have household and familial responsibilities. Despite more work (paid and unpaid) for longer hours when compared to male farmers, women farmers can neither make any claim on output nor ask for a higher wage rate. An increased work burden with lower compensation is a key factor responsible for their marginalisation. It is important to have gender-friendly tools and machinery for various farm operations. Most farm machinery is difficult for women to operate. Manufacturers should be incentivised to come up with better solutions. Farm machinery banks and custom hiring centres promoted by many State governments can be roped in to provide subsidised rental services to women farmers.

Last, when compared to men, women generally have less access to resources and modern inputs (seeds, fertilizers, pesticides) to make farming more productive. The Food and Agriculture Organisation says that equalising access to productive resources for female and male farmers could increase agricultural output in developing countries by as much as 2.5% to 4%. Krishi Vigyan Kendras in every district can be assigned an additional task to educate and train women farmers about innovative technology along with extension services.

As more women are getting into farming, the foremost task for their sustenance is to assign property rights in land. Once women farmers are listed as primary earners and owners of land assets, acceptance will ensue and their activities will expand to acquiring loans, deciding the crops to be grown using appropriate technology and machines, and disposing of produce to village traders or in wholesale markets, thus elevating their place as real and visible farmers.

Seema Bathla and Ravi Kiran are Professor and research scholar, respectively, at the Centre for the Study of Regional Development, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi

Source: The Hindu, 15/10/2018

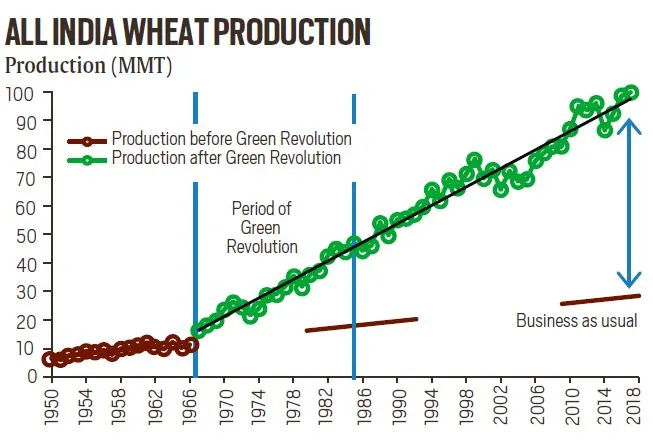

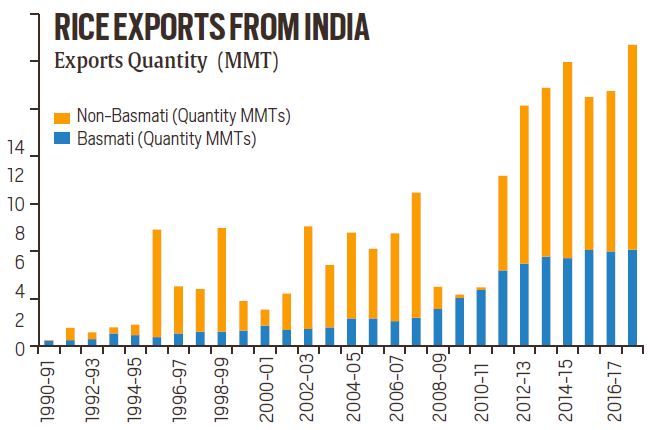

Source: Agricultural Statistics at a Glance, Department of Agriculture, Cooperation and Farmers Welfare, Government of India, Agricultural Processing and Export Development Authority (APEDA), Government of India.

Source: Agricultural Statistics at a Glance, Department of Agriculture, Cooperation and Farmers Welfare, Government of India, Agricultural Processing and Export Development Authority (APEDA), Government of India. Source: Agricultural Statistics at a Glance, Department of Agriculture, Cooperation and Farmers Welfare, Government of India, Agricultural Processing and Export Development Authority (APEDA), Government of India.

Source: Agricultural Statistics at a Glance, Department of Agriculture, Cooperation and Farmers Welfare, Government of India, Agricultural Processing and Export Development Authority (APEDA), Government of India.