When former Prime Minister Dr Manmohan Singh in 2010 flagged Naxalism as the important internal security challenge, the insurgency was at its peak. In line with that assessment, the government of India reinforced security and development assistance to state governments faced with this problem. This combined effort is yielding positive results. The number of civilians and security forces killed has come down. So is the number of severely affected districts, which are no more than 30. What is catastrophic though is the sporadic high fatalities suffered by security forces in the well-planned offensive ambushes laid by Naxalites. Is this an insurmountable challenge? Analysing this menace from ideological, strategical and tactical frameworks is likely to throw some convincing answers.

According to Maoist ideology, economically oppressed peasants/working class will triumph over the oppressive capitalist bourgeois class to establish a classless society. For them, the only strategy to establish a classless society is through armed revolution. The operational tactics to give shape to that strategy is protracted guerrilla warfare.

The ideological fountain of Maoism, class struggle, that erupted as a small armed rebellion between the landless peasants and the landed aristocracy in Naxalbari village in West Bengal in 1967, could not sustain. Rapid economic growth, aspirational youth and opportunities created by communication and mobility act as a strong counter for economic class-based division.

The strategy of organising the oppressed class into a people’s army and a bottom-up approach of encircling the urban areas from the hinterland periphery to overthrow the ruling elite, remained a pipe-dream. If anything, armed class struggle which appeared to be taking roots in north Telangana, Srikakulam of Andhra Pradesh and south Vidarbha in the1980s, instead of expanding from villages to urban centres has retreated further into the core forested area.

With their ideology and strategy not getting much traction, the Maoists are seemingly succeeding in their tactics. It is showing in the support and sustenance Maoists receive from the local population and their ability to mobilise their village defence forces and armed dhalams into a kind of mobile army for a virulent attack. This is the nature of mobile guerrilla warfare. Fortunately for the security forces, the so-called liberated zone is confined to about 50,000 sqkm of forested area of Bastar, Bijapur, Dantewada, Kanker, Kondagaon, Narayanpur and Sukma districts of Chhattisgarh, with little spillover into adjoining Maharashtra and Odissa.

Strategic victory over them calls for clarity on the role and responsibility of the central and state and governments; honest assessment of capabilities, operational philosophy, mindset, willingness, compulsions and resolve of security forces involved in anti-Naxalite operations; and a realistic timeframe to root out this menace.

This warfare at the tactical level can be successfully fought by an equally agile, stealthy, enduring and disciplined commando force of the state police, recruited trained and raised primarily out of the local youth. The most acclaimed of such a commando force is the Greyhounds of erstwhile Andhra Pradesh police. This is a success story to build on.

Achieving strategic victory is no guarantee for lasting peace. Maoism is a social, economic and developmental issue manifesting as a violent internal security problem. Even the Maoists would like the state to respond from security rather than developmental perspective, as they know that only in relative poverty and severe infrastructure deficit, they have their captive support base of the population.

It is not merely for tactical reasons the Maoist influence thrives in contiguous forested areas spread over Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, Maharashtra, Orissa, Telangana and Andhra Pradesh. There is a deep-rooted financial interest. This region is richly endowed with minerals of bauxite, iron ore, limestone, marble, dolomite, coal and copper and of pristine forests rich in timber and Minor Forest Produce (MFP). The MFP, which includes bamboo and tendu leaf (for rolling beedi), contrary to the nomenclature is a huge source of revenue estimated at over Rs 20,000 crore a year. The value chain in these natural resources leaves a huge profit margin for the extractive industry/contractors and scope for extortion/protection money to the Maoists. The unit of auction for extraction of MFP is a block of forest area. Quantity extracted out of a block is left to the ability of the contractor, thus leaving huge profit. The Maoists pose as RoWith many state governments notifying the Panchayat (Extension of Scheduled Areas) Act 1996, the gram panchayats now auction the MFP, including bamboo and tendu leaves. Thus, substantial revenue goes to the village panchayats for development works. In theory, it is the most decentralised and financially empowered local self-government model. With little institutional support, it needs an independent study on the ability of the tribal village panchayats in managing these entrenched bunch of contractors, threats posed by Naxalites and possibilities it leaves for extortion. It is not for nothing that the panchayat elections are keenly contested in the Naxal-affected districts and the Naxalites, who are otherwise against electoral democracy, generally do not disturb these elections.

A national policy to end Naxalist violence has to emanate out of economic, developmental and internal security considerations. There has to be a judicious and environmentally sustainable extraction of natural resources, leaving no scope for value capture by unscrupulous elements. An integrated approach spearheaded by counter-offensive operations led by well trained, disciplined, agile and stealthy commando force of state police; expansion of road networks from the periphery to core of liberated zone constructed under security cover of central forces or even constructed by the specially raised engineering units of central forces; quick expansion of mobile communication and commercialisation of economic activities are slow but sure and irrevocable process to success.

Written by Jaganathan Saravanasamy

(The writer is additional DGP (Planning & Coordination), Maharashtra State Police)bin Hoods by seemingly negotiating a better wage for the labour or price for the produce.

Source: Indian Express, 21/04/21

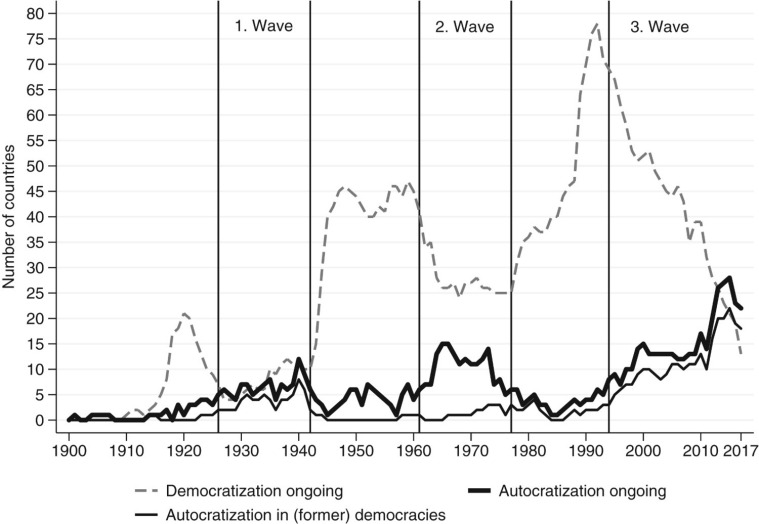

The three waves of autocratisation as mapped by Anna Lührmann and Staffan I. Lindberg. (Source: research paper by Anna Lührmann and Staffan I. Lindberg)

The three waves of autocratisation as mapped by Anna Lührmann and Staffan I. Lindberg. (Source: research paper by Anna Lührmann and Staffan I. Lindberg)