Followers

Monday, November 29, 2021

Current Affairs- November 25, 2021

INDIA

ECONOMY & CORPORATE

WORLD

Online courses that will help you learn the dynamics of Indian Constitution

While the Constitution is self-explanatory, the charter language often confuses aspirants. Various platforms host online workshops as well as courses on key features of the Indian Constitution, which can be a good way to understand it in a simple and jargon-free manner.

On November 26, 1949, the Constituent Assembly adopted the Constitution of India, and it came into effect on January 26, 1950. Seventy-two years later, the Constitution of India has added several amendments, sections, and articles.

To spread awareness on various mandates of the Constitution, several bodies that conduct competitive examinations still give high weightage to the topic.

The syllabus of the UPSC Civil Service, SSC-CGL, NDA and other such examinations intensely covers the Indian Constitution in all stages of the test. In recent years, the UPSC preliminary exam has had at least 7-8 questions on the Constitution whereas, in the mains, the topic is largely covered in the GS II syllabus. This makes reading and understanding the Indian Constitution a prerequisite for qualifying the exam.

While the Constitution is self-explanatory, the charter language often confuses aspirants. Various platforms host online workshops as well as courses on key features of the Indian Constitution, which can be a good way to understand it in a simple and jargon-free manner.

Course on the Indian Constitution – Ministry of Law & Justice, NALSAR Hyderabad

The Department of Legal Affairs, Ministry of Law & Justice, in collaboration with NALSAR University of Law, Hyderabad, has launched an online course on the Indian Constitution which will be available on the website at legalaffairs.nalsar.ac.in. The registration for this course is free of cost. However, for those who wish to obtain a certificate of appreciation or certificate of merit, a token fee of Rs 100 will be charged, as per an official statement. The online course has 15 conceptual videos and the first video lecture shall be available upon registration.

Constitution of India – Udemy

Udemy, an online learning platform, offers a “Constitution of India” course. The course highlights key features of the Indian Constitution and aims at providing general awareness about the Indian Constitution. Some of the topics are read like a podcast so as to provide learners with the feel of audiobooks.

Indian Polity and Constitution – Udemy

Similarly, another programme, “Indian Polity and Constitution’ course at Udemy covers the detailed concept of constitutional framework, system of government, constitutional and non-constitutional bodies etc. The programme is specifically designed for competitive exam aspirants. The course is divided into 51 lectures spanning approximately three hours. The participants are provided with a certificate on completion of the course.

Constitutional law in 90 minutes – Udemy

If you are short of time and need a fast-track summary of the constitutional framework then ‘Constitutional Law in 90 Minutes’ is the course for you. The course can be helpful for law students as well as students opting for law optional at the UPSC Civil Service exam. This course will give you a “bird’s eye” overview of the entire subject.

The Constitution of India (Part 1) – Finology learn

Finology learn provides an elaborative course to understand the drafting and implementation of important provisions of the Constitution. The course offers 20 modules covering 60+ topics. The modules are provided through video lectures and comprehensive notes and a certificate is provided to studentFundamental Rights in the Indian Constitution – My law

This course provides a detailed understanding of what fundamental rights mean, their purpose in the Constitution, and how the Supreme Court of India has interpreted them.

In addition to unit-wise practise exercises, this course offers a Course Completion Test (CCT). To qualify for the CCT, a learner has to complete more than 90 per cent of the course. The CCT is conducted online to provide maximum flexibility to the learner. Based on the results of the CCT, a learner will be given a certificate, which is recognised by various employers in the legal industry.s on completion of the course.

Source: Indian Express, 27/11/21

What meeting MSP demand would cost govt

The unions want the Modi government to enact legislation conferring mandatory status to MSP, rather than just being an indicative or desired price.

Why are the unions seeking legal guarantee for MSP?

The Centre currently announces the MSPs of 23 crops. They include 7 cereals (paddy, wheat, maize, bajra, jowar, ragi and barley), 5 pulses (chana, tur/arhar, moong, urad and masur), 7 oilseeds (rapeseed-mustard, groundnut, soyabean, sunflower, sesamum, safflower and nigerseed) and 4 commercial crops (sugarcane, cotton, copra and raw jute). While the MSPs technically ensure a minimum 50% return on all cultivation costs, these are largely on paper. In most crops grown across much of India, the prices received by farmers, especially during harvest time, are well below the officially-declared MSPs. And since MSPs have no statutory backing, they cannot demand these as a matter of right. The unions want the Modi government to enact legislation conferring mandatory status to MSP, rather than just being an indicative or desired price.

How can that entitlement be implemented?

There are basically three ways.

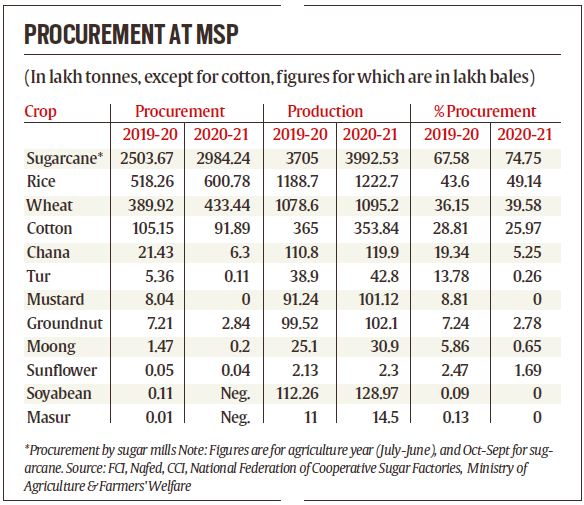

The first is by forcing private traders or processors to pay MSP. This is already applicable in sugarcane. Sugar mills are required, by law, to pay farmers the Centre’s “fair and remunerative price” for cane, with some state governments fixing even higher so-called “advised prices”. The Sugarcane (Control) Order, 1966 issued under the Essential Commodities Act, moreover, obliges payment of this legally-guaranteed price within 14 days of cane purchase. During the 2020-21 sugar year (October-September), mills crushed some 298 million tonnes (mt) of cane, which, the accompanying table shows, was close to three-fourths of the country’s estimated total production of 399 mt.

The second is by the government undertaking procurement at MSP through its agencies such as the Food Corporation of India (FCI), National Agricultural Cooperative Marketing Federation of India (Nafed) and Cotton Corporation of India (CCI). As can be seen from the table, such purchases accounted for nearly 50% of India’s rice/paddy production last year, while amounting to 40% for wheat and over 25% in cotton. Government agencies also bought significant quantities – upwards of 0.1 mt – of chana (chickpea), mustard, groundnut, tur (pigeon-pea) and moong (green gram) during 2019-20. Much of that was post the Covid-induced nationwide lockdown in April-June 2020, when the winter-spring rabi crops were being marketed by farmers. Procurement of these crops, however, fell in 2020-21. In the case of mustard, tur, moong, masur (yellow lentil) and soyabean, the need for procurement wasn’t really felt, as open market prices largely ruled above MSPs.

The second is by the government undertaking procurement at MSP through its agencies such as the Food Corporation of India (FCI), National Agricultural Cooperative Marketing Federation of India (Nafed) and Cotton Corporation of India (CCI). As can be seen from the table, such purchases accounted for nearly 50% of India’s rice/paddy production last year, while amounting to 40% for wheat and over 25% in cotton. Government agencies also bought significant quantities – upwards of 0.1 mt – of chana (chickpea), mustard, groundnut, tur (pigeon-pea) and moong (green gram) during 2019-20. Much of that was post the Covid-induced nationwide lockdown in April-June 2020, when the winter-spring rabi crops were being marketed by farmers. Procurement of these crops, however, fell in 2020-21. In the case of mustard, tur, moong, masur (yellow lentil) and soyabean, the need for procurement wasn’t really felt, as open market prices largely ruled above MSPs.

Generally speaking, MSP implementation has been effective only in four crops (sugarcane, paddy, wheat and cotton); partly so in five (chana, mustard, groundnut, tur and moong) and weak/non-existent in the remaining 14 notified crops. In livestock and horticultural produce – be it milk, eggs, onions, potatoes or apples – there is no MSP even on paper! The 23 MSP crops together, in turn, account for hardly a third of the total value of India’s agricultural output, excluding forestry and fishing.

The third route for guaranteeing MSP is via price deficiency payments. Under it, the government neither directly purchases nor forces the private industry to pay MSP. Instead, it allows all sales by farmers to take place at the prevailing market prices. Farmers are simply paid the difference between the government’s MSP and the average market price for the particular crop during the harvesting season.

What would be the fiscal cost of making the MSP legally binding?

The MSP value of the total output of all the 23 notified crops worked out to about Rs 11.9 lakh crore in 2020-21. But this entire produce wouldn’t have got marketed. The marketed surplus ratio – what remains after retention by farmers for self-consumption, seed and feeding of animals – is estimated to range from below 50% for ragi and 65-70% for bajra (pearl-millet) and jowar (sorghum), to 75-85% for wheat, paddy and sugarcane, 90%-plus for most pulses and 95-100% for cotton, soyabean, sunflower and jute. Taking an average of 75% yields a number – the MSP value of production actually sold by farmers – just under Rs 9 lakh crore.

The government is further, as it is, procuring many crops. The MSP value of the 89.42 mt of paddy and 43.34 mt of wheat alone bought during 2020-21 was around Rs 253,275 crore. To this, one must add the MSP value of pulses and oilseeds purchased by Nafed (Rs 21,901 crore in 2019-20 and Rs 4,948 crore in 2020-21) and kapas or raw un-ginned cotton by CCI (Rs 28,420 crore in 2019-20 and Rs 26,245 crore in 2020-21). Besides, the MSP value of the sugarcane crushed by mills (Rs 92,000 crore in 2020-21) has to be considered.

All in all, then, the MSP is already being enforced, directly or through fiat, on roughly Rs 3.8 lakh crore worth of produce. Providing legal guarantee for the entire marketable surplus of the 23 MSP crops would mean covering another Rs 5 lakh crore or so. It would be even lower, given two things. The crop that is bought by the government also gets sold, with the revenues from that partly offsetting the expenditures from MSP procurement. Secondly, government agencies needn’t buy every single grain coming in to the mandis. Mopping up even a quarter of market arrivals is often enough to lift prices above MSPs in most crops.

But there must be a catch to all these calculations?

Yes. FCI’s grain mountain is evidence of how cumbersome public procurement and stocking operations can be. This is not to mention the huge scope for corruption and recycling/leakage of wheat and rice, whether from godowns, ration shops or in transit. Also, while cereals and pulses can be sold through the public distribution system, disposal becomes complicated in the case of nigerseed, sesamum or safflower. Even when it comes to sugarcane, the experience of mills accumulating huge payment arrears to growers is proof of the practical limitations of “legal MSP”.

That leaves deficiency payments, which may be a more workable and fiscally feasible option in the long run. There is, in addition, a growing consensus among economists for guaranteeing minimum “incomes”, as against “prices”, to farmers. That would essentially entail making more direct cash transfers either on a flat per-acre (as in the Telangana government’s Rythu Bandhu scheme) or per-farm household (the Centre’s PM-Kisan) basis.

Written by Harish Damodaran

Source: Indian Express, 29/11/21

Why it has been named Omicron and not Nu or Xi

The WHO has been using Greek letters to refer to the most widely prevalent coronavirus variants, which otherwise carry long scientific names.

In picking a name for the newest variant of SARS-CoV-2, Omicron, the World Health Organization (WHO) has skipped two letters of the Greek alphabet, one of which also happens to be a popular surname in China, shared even by Chinese President Xi Jinping.

The WHO has been using Greek letters to refer to the most widely prevalent coronavirus variants, which otherwise carry long scientific names. It had already used 12 letters of the Greek alphabet before the newest variant emerged in South Africa this week. After Mu, the 12th named after a Greek letter, WHO selected the name Omicron, instead of Nu or Xi, the two letters between Mu and Omicron.

The WHO said Nu could have been confused with the word ‘new’ while Xi was not picked up following a convention.

“Two letters were skipped —Nu and Xi — because Nu is too easily confounded with ‘new’ and XI was not used because it is a common surname and WHO best practices for naming new diseases (developed in conjunction with FAO and OIE back in 2015) suggest avoiding ‘causing offence to any cultural, social, national, regional, professional or ethnic groups’,” the WHO said in a statement.

All variants are given scientific names that represent their parentage and the chain of evolution. Omicron, for example, is also known by its more scientific designation B.1.1.529, which shows that it has evolved from the B.1 lineage.

Since the scientific names are not easy to remember, the more prevalent variants started to be named after the country from where they were first reported: ‘UK variant’, ‘Indian variant’, ‘South African variant’, or ‘Brazilian variant’. To remove the connection with specific countries, which was triggering name-calling and blame game, the WHO decided on a new naming system using Greek letters. The variant that earlier used to be referred as the ‘Indian’ thus got the name Delta, while the one being associated with the UK was named Alpha.

Over the course of the pandemic, many variants of the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus have arisen, the latest being Omicron in South Africa.

WHAT IT MEANS

As an infected cell builds new coronaviruses, it occasionally makes tiny copying errors. These called mutations. Mutations are passed down through a lineage, a branch of the viral family tree. A group of coronaviruses that share the same inherited set of distinctive mutations is called a variant.

VARIANTS OF CONCERN

The WHO currently lists 5 variants of concern:

- Omicron (B.1.1.529), identified in southern Africa in November 2021

- Delta (B.1.617.2), which emerged in India in late 2020 and spread around the world

- Gamma (P.1), which emerged in Brazil in late 2020

- Beta (B.1.351), which emerged in South Africa in early 2020

- Alpha (B.1.1.7), which merged in Britain in late 2020

- VARIANTS OF INTEREST

There are currently two:

- Mu (B.1.621), which emerged in Colombia in early 2021

- Lambda (C.37), which emerged in Peru in late 2020

Baroda in Mumbai and Patna in Scotland: What place names can tell us about migration, assertion of power

As people migrate, they carry with themselves names of the places they left behind, or cultural motifs, historical figures and much more.

Poring over newspaper archives at the Nehru Memorial Library in Delhi last month for a project on post Independent India, I chanced upon a tiny article in the Hindustan Times, dated August 8, 1947. The Madras government had decided to “re-Indianise the names of towns and cities in the province which have undergone a change during the British rule,” reported the article. These were the days preceding the Independence and the renaming spree was hardly surprising. What struck me though was a line in the piece that said, “it is likely that the capital of the province will shed the Portuguese name of Madras and be renamed as Chennapatnam.”

As one of the three presidencies under the British government, the influence of the English on Madras was well known. But its name carried reminiscences of a different past, one before the East India Company, wherein the waters of the Indian Ocean had welcomed several groups of traders, explorers, proselytisers from across the world. The Portuguese were the first to arrive and had established several settlements along the Coromandel Coast. Although subject to contention, the name Madras is believed to be derived from Madre de Sois, a Portuguese high authority and one of the earliest settlers in the region.

Place names are important repositories of historical and cultural processes. They provide interesting and often overlooked details about the political mood in a region. They are also fascinating testimonies of the movement of people and their communities. As people migrate, they carry with themselves names of the places they left behind, or cultural motifs, historical figures and much more.

Why does this happen? Professor Anu Kapur, who has also authored the book, ‘Mapping place names of India’ says there are multiple reasons. “Firstly, there is a sense of finding familiarity in a new place. Secondly, it is also about power establishment in a place. Third, when a community gets established in a new place, it likes to reinforce its presence by putting on display every other cultural symbol. Names are also part of the process of symbol creation just like religious spaces, food stalls and the like,” she says.

Taken together, these names that are a product of migration, have much to say about the ways in which people from near and far have moved around the subcontinent and have produced a rich and variegated cultural fabric in the country.

Recreating a home left behind

The replication of names from their homeland in a new place is a fairly common way in which a migrant community creates a familiar environment. Kapur in her book provides the example of the Moplah Muslim peasants of the Malabar region who were sentenced to life imprisonment in the Andaman Penal Colony for revolting against the British in the 19th century. In the Andaman Islands they named their villages Calicut, Wandur, Tirur, Manjeri, Malappuram, Manarghat and Nilambur, after the names of their native villages in South Malabar.

In Mumbai, where a large group of trading communities settled down after the British developed the group of islands into a centre of commerce, there exists several streets named after towns in Western India, indicative of the active inter-regional trade. “When the East India Company came to Bombay, the idea was to eventually relocate from Surat because it was getting too politically unstable, and find a trading outpost closeby. The only way to develop trade in Bombay was to encourage trading communities from Surat and its vicinity to resettle in Bombay,” says Sifra Lentin, Bombay History Fellow at Gateway House. “Immigrants from Gujarat were in fact the first to come to Bombay during the Company period. They were guaranteed religious freedom, tax benefits and other such incentives,” she adds.

The early Gujarati presence in Bombay is perhaps the reason why we come across Baroda Street in East Mumbai. Samuel Townsend Sheppard in a book published in 1917 suggests the presence of an Ahmedabad Road constructed by the Bombay Port Trust in 1883 and named after the city in Gujarat. There is also a Karwar street in the Fort area of the city, named after the city in Karnataka. Lenin suggests that it is also possible “these streets near the dockyards were developed by the Bombay Port Trust and came up because of the logistics of warehousing as per the region of origin”.

Yet another example of a street name being reproduced is the Charni Road in South Mumbai. Sheppard in his book notes that this name Charni or Chendni was brought to the locality from Thana. “The locality near Thana Railway Station is called Chendni and many inhabitants of Chendni in Thana came and permanently settled in Girgaum, in Bombay, and so called the locality where they settled Chendni,” he writes.

In Delhi too, where the forces of migration have practically built the city, we do come across a few names carried across by communities from their native places. Historian Narayani Gupta, in her article ‘Delhi’s history as reflected in its toponymy’ (2010), notes about settlements that developed in the agricultural lands of the city bearing the names given by people who came and settled there. “In some cases they carried the name of a village they had left, and gave it to the place they settled in. There are some beautiful names which might well have originated elsewhere, or had a meaning in a local dialect,” she writes along with examples such as Holambi, Mehrauli, Kondli, Mundhela, Okhla, Jasola, Malcha, Munirka, Karkardooma, Karkari among several others.

The influx of refugees into Delhi after Partition resulted in many neighbourhoods being established with the specific objective of settling them. While a majority of them were named after nationalist icons, there were a few named after the towns the refugees left behind as well like Dera Ismail Khan and Gujranwala which are places in the North West Frontier Province.

If not the name of a place, then it is a motif from their homes that found a place in the new city, as was the case with Pamposh Enclave, a neighbourhood in South Delhi inhabited by Kashmiri Pandits. Pamposh in Kashmiri means lotus, which grows in abundance in the valley, and has a special place in the collective identity of this group of migrants in Delhi.

Migrants from East Pakistan who settled in the Andaman Islands after 1947 too carried with them names that are common in their homeland. Durgapur, Shibpur, Madhyamgram, Kalighat, Bijoygarh among others are names of places in Bengal that have been replicated in the Andamans.

Similarly, names have travelled from India to other parts of the world as well. Take for instance the case of Patna, a village in East Ayrshire, Scotland. As per records, the village was established in 1802 by William Fullarton, a Scottish soldier, statesman and author. Fullarton was born in Patna in Bihar, where his father was an employee with the East India Company. He named the village in Scotland as a tribute to his place of birth.

The presence of Phra Nakhon Si Ayutthaya in Thailand, deriving its name from Ayodhya, is evidence of the spread of Hinduism through trade and migration across large parts of SouthEast Asia.

In the name of those with power and influence

Yet another way in which a migrant community exerts its presence in a new place is when someone from amongst them carries enough influence to have a place named after him or her. This, for instance, is the case with Samuel Street in Mumbai. “This road is named after a Bene Israeli native commandant named Samuel Ezekiel Divekar. This was the place where the Bene Israel Jews first settled when they came for job opportunities in the native military regiment and where they built Bombay’s first synagogue in 1796,” explains Lentin. She says that the street got named after Divekar who took part in the Second Mysore War and was decorated for it.

The Jewish community’s presence in Kolkata is remembered by the presence of Ezra Street. In the late 18th century, a large group of mercantile Baghdadi Jews had moved to Calcutta in the hope of finding trading prospects. The Ezra family is believed to have been the wealthiest amongst the Calcutta Jews. Although there exists a debate over whether the street was named after David Joseph Ezra or his son Elias David Ezra, there is no dispute over the kind of influence the father and son held in the city. David Joseph Ezra was a trader in indigo and silk. He invested the profits he made in building large colonial mansions, many of which continue to exist in the city. His son built the 137-year old Maghen David Synagogue in memory of his father that stands on one end of Ezra Street.

The Marwaris from Rajasthan were yet another enterprising migrant community that built large parts of Kolkata. The Marwari presence and contribution in the city is evident from the number of schools, hospitals, temples and other such establishments built by them. Equally noteworthy are the streets that came to be named after prominent members of the community such as the Hari Ram Goenka Street in Bara Bazaar. Hari Ram Goenka was the grand uncle of Rama Prasad Goenka, founder of the RPG group. The former was conferred knighthood by the British for his outstanding contribution to Indian commerce.

“Unlike large parts of colonial India like Bombay, Madras or Pondicherry where communities moved in on the encouragement of the colonisers who then laid out the city along community lines, in Calcutta trading and other migratory groups came in long before colonial rule,” explains Kolkata-based historian Tathagatha Neogi, who also runs the heritage walks organisation ‘Immersive Trails’. Consequently, unlike in these other cities where specific neighbourhoods were named after the community living there, in Calcutta no such street exists other than the Armenian Street. The remarkable migrant presence in the city can be felt through the names of influential members of the community. “There are many streets in Kolkata that are named after important cooks. For instance, there is a small street in Sealdah called Chhaku Khansama Lane, named after a well known cook. A majority of them were Muslims from Uttar Pradesh or Bihar,” says Neogi.

In the name of colonial ambitions

From the 17th century onwards, as Europeans set out to explore and exploit territories across the world, they left their mark in the lexicon of place names of the countries which they brought under their control. In the case of colonial migration place names were made use of not just for cultural reinforcement, but also for establishing supremacy. The Portuguese named the port town of Goa as Vasco Da Gama after the explorer who was the first to arrive in India at Calicut. Till date, Vasco remains a popular name in Goa.

The Danish East India Company which arrived in India in the mid 17th century set up a commercial unit in the Nicobar islands, which they called Frederic’s Islands in honour of Frederick V, the king of Denmark-Norway. “Among the Danes it was common to name the colonised after their royal family or native land,” writes Kapur. She writes that “the diary of a missionary serving in the Nicobar Islands in 1770 informs us that the Danes had named these islands New Denmark.” Similarly, Serampore in West Bengal, where the Danes had another settlement, was named Frederiksnagore after the Danish King.

The French colonial presence in Pondicherry ‘s history is palpable in the existing division of the city between the ‘white town’ and ‘black town’. Interestingly, large parts of the white town continues to be strewn across with street names carrying the prefix ‘rue de’, meaning ‘street of’ in French. Yet another way in which the French planned the city was to establish separate neighbourhoods for the communities such as Vellala Street, Chetty street, Kômutti street, Vannara street and the like. Author Ari Gautier, who has written several historical fiction books on Pondicherry, explains that the French brought in people from across Southern India to work in the new settlement as traders, weavers, merchants and employees in the French government. In order to settle them, they built separate streets segregating them on caste and community lines. “Vellalar, for instance, is an agricultural community living around the Immaculate church. But during the colonial period they shifted their traditional profession to become part of the French administration,” says Gautier. “Kômutti is another branch of Chettiars, mostly from Andhra Pradesh. Vannaras are the washerman caste from Tamil Nadu.”

The Portuguese, Danes and French left their names, but were largely restricted to certain pockets and definitely pale in front of the impact of the British in naming places in India. “Economic exploitation was the primary aim of the British in taking over India. This intention had manifested itself in their scheme of changing the place names of the country,” writes Kapur. She makes a distinction between the two ways in which the British impacted place names in India. One was in the nature of Englishisation and the other was in the spirit of Anglicisation. In case of the former, personal English names and words were introduced, for instance the names of hill stations like Dalhousie and McLeodganj. In case of the latter, the spellings of a few names were changed to suit British pronunciation.

Nowhere does the British intention of exerting their authority through place names become as evident as that in their building of New Delhi after the shift of the capital from Calcutta in 1911. At the heart of the new city was Kingsway, a ceremonial boulevard sweeping down from the Viceroy’s House, named after a major road in central London. This road was bisected by yet another road named after a street in London called Queensway. Historian Swapna Liddle, in her book ‘Connaught Place and the making of New Delhi’, explains that in the New Delhi of the British, roads housing those from the higher echelons of the government were named after the British monarchs like King Edward Road, Queen Victoria Road, and King George’s Avenue. Then there were streets named after those who had played a special role in the governance and establishment of the British Empire such as Clive Road, Curzon Road, Hastings Road among others. Interestingly, the British laid out alongside streets named after the erstwhile Indian monarchs such as Ashoka Road, Akbar Road, Aurangzeb Road and Shah Jahan Road. The purpose was clearly to establish the fact that though the British were outsiders, their imperial ambitions were on the same lines as that occupied by the high and mighty of Indian history.

Further reading:

Anu Kapur, Mapping place names of India, Taylor and Francis, 2019

Narayani Gupta, Delhi’s history as reflected in its toponymy, in ‘Celebrating Delhi’, Mala Daya (ed.) Penguin Books Limited, 2010

Samuel Townsend Sheppard, Bombay place-names and street-names; an excursion into the by-ways of the history of Bombay City, Times Press, 1917

Swapna Liddle, Connaught Place and the making of New Delhi, Speaking Tiger Books, 2018

Written by Adrija Roychowdhury

Source: Indian Express, 26/11/21

Friday, November 26, 2021

Quote of the Day November 26, 2021

“If you end with a boring miserable life because you listened to you mom, your dad, your teacher, your priest, or some guy on television, then you deserve it.”

Frank Zappa

“अगर आप अपनी मां, अपने पिता, अपने शिक्षक, अपने पुजारी, या टीवी पर किसी अजनबी की सुनने के कारण एक उबाऊ और दुखी जीवन जीते हैं, तो आप इसी लायक हैं।”

फ़्रेंक ज़ाप्पा