What is the root of the conflict?

During British rule, undivided Assam included present-day Nagaland, Arunachal Pradesh, Meghalaya and Mizoram. Meghalaya was carved out in 1972, its boundaries demarcated as per the Assam Reorganisation (Meghalaya) Act of 1969, but has held a different interpretation of the border since.

In 2011, the Meghalaya government had identified 12 areas of difference with Assam, spread over approximately 2,700 sq km.

Some of these disputes stem from recommendations made by a 1951 committee headed by then Assam chief minister Gopinath Bordoloi. For example, a 2008 research paper from the Manohar Parrikar Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses refers to the Bordoloi Committee’s recommendation that Blocks I and II of Jaintia Hills (Meghalaya) be transferred to the Mikir Hill (Karbi Anglong) district of Assam,, besides some areas from Meghalaya’s Garo Hills to Goalpara district of Assam. The 1969 Act is based on these recommendations, which Meghalaya rejects, claiming that these areas originally belong to the Khasi–Jaintia Hills. On the other hand, Assam says Meghalaya does not have the requisite documents to prove these areas historically belonged to Meghalaya.

A number of attempts had been made in the past to resolve the boundary dispute. In 1985, under then Assam chief minister Hiteswar Saikia and Meghalaya chief minister Captain W A Sangma, an official committee to resolve the issue was constituted under the former Chief Justice of India Y V Chandrachud. However, a solution was not found.

Key turn but twists ahead

Meghalaya was carved out of Assam in 1972, and has held a different interpretation of the border since. The resolution at six of the 12 areas under dispute is significant, but the remaining points of friction are more complex and may prove to be a bigger challenge.

What is the current pact?

Since July last year, Assam Chief Minister Himanta Biswa Sarma and his Meghalaya counterpart Conrad Sangma have been in talks to solve the long-standing dispute.

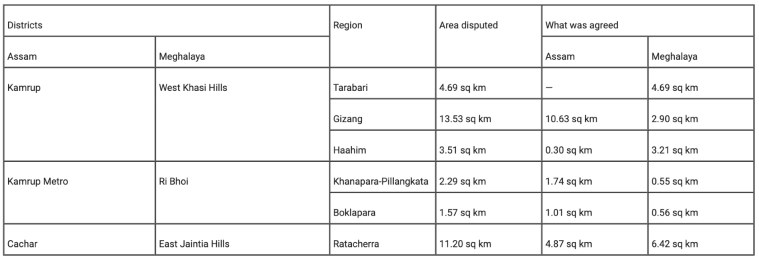

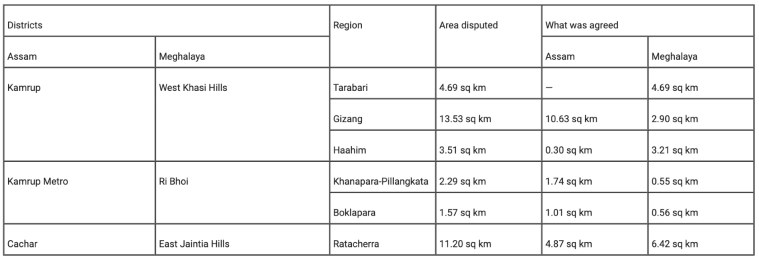

Both state governments identified six out of 12 disputed areas for resolution in the first phase: 3 areas contested between West Khasi Hills district in Meghalaya and Kamrup in Assam, 2 between RiBhoi in Meghalaya and Kamrup-Metro, and 1 between East Jaintia Hills in Meghalaya and Cachar in Assam.

After a series of meetings and visits by teams to the disputed areas, both sides submitted reports based on five mutually agreed principles: historical perspective, ethnicity of local population, contiguity with boundary, peoples’ will and administrative convenience.

A final set of recommendations were made jointly: out of 36.79 sq km of disputed area taken up for settlement in the first phase, Assam would get full control of 18.46 sq km and Meghalaya of 18.33 sq km. The MoU signed on Tuesday was based on these recommendations.

So, who gets what?

From the 2011 claims made by Meghalaya government, an area of roughly 36.79 sq km was taken up for resolution in the first phase.

According to presentations by both states, the area has been roughly divided into equal parts, and a total of 30 sq km is being recommended to be within Meghalaya.

What are the next steps?

The next step will involve delineation and demarcation of the boundary by Survey of India in the presence of representatives of both governments. It will then be put up in Parliament for approval. The process may take a few months.

Officials said six areas taken for study did not have large differences and were easier to resolve, and were hence taken up in the first phase. “The remaining six areas are more complex and may take longer to resolve,” said an Assam government official.

Is there any opposition?

Former Meghalaya CM Mukul Sangma, who is now part of the Trinamool Congress that is the principal opposition party in Meghalaya, criticised the government’s approach. “This is a piecemeal resolution. They have taken up only 36 sq km for resolution. The larger, more complex areas (such as Langpih, Block I and II) are yet to be resolved and it will not be so easy,” he said. “The reality on ground zero is different – as far as I know, many people have not accepted the settlement and the agreement is almost like an imposition,” he said.

In Assam, too, Opposition leaders criticised the state government for rushing through the issues, and not consulting stakeholders. In January, Leader of Opposition Debabrata Saikia of the Congress had alleged that CM Sarma had gone ahead and submitted a proposal to the Union Home Minister “without even a discussion in the State Assembly.” “This is irresponsible and unconstitutional,” said Saikia, asking that the recommendations be rescinded and demanding a special session in the Assembly.

Written by Tora Agarwala ,

Source: Indian Exprss, 1/04/22