2020-21 was one of Indian agriculture’s finest moments, as memorable as 1967-68 that inaugurated the Green Revolution. While much of the country was locked out of economic activity in Covid-19’s first and second waves, farmers not only harvested their standing rabi crop from late March 2020 but also planted aggressively for the next two seasons. Agriculture was the only sector to grow 3.3 per cent in 2020-21, even as the economy overall contracted by 4.8 per cent. According to the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy’s Mahesh Vyas, the farm sector added 3.4 million jobs in 2020-21 and 11 million from 2019-20 to 2021-22. During these three years, the rest of the economy shed 15 million jobs.

But 2020-21 and the year that followed were also remarkable for a related phenomenon – of India’s public distribution system (PDS) truly coming of age and delivering at a time of crisis. Sales of rice and wheat under various government schemes totalled 92.9 million tonnes (mt) in 2020-21 and 105.6 mt in 2021-22. This was as against an average offtake of 62.5 mt during the first seven years after the implementation of the National Food Security Act (NFSA) in 2013-14 and 48.4 mt in the seven years preceding the legislation.

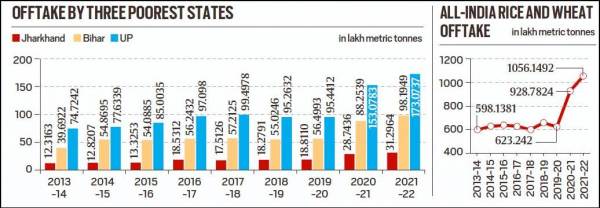

The accompanying charts show the offtake of rice and wheat both at the all-India level and for the three poorest states as per the NITI Aayog’s National Multidimensional Poverty Index — Bihar, Jharkhand and Uttar Pradesh (UP). All three registered significant increases in offtake levels post-NFSA between 2013-14 and 2019-20: Jharkhand (from 1.2 mt to 1.9 mt), Bihar (4 mt to 5.6 mt) and UP (7.5 mt to 9.5 mt). These have further risen post-Covid, to 3.1 mt for Jharkhand, 9.8 mt for Bihar and 17.3 mt for UP in 2021-22.

The NFSA legally entitles up to 75 per cent of India’s rural and 50 per cent of the urban population — translating into some 813.5 million people — to receive 5 kg of grain per person per month at highly subsidised rates of Rs 2/kg for wheat and Rs 3/kg for rice. In the wake of the Covid-induced economic disruptions, a new Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Anna Yojana (PMGKAY) scheme was launched giving NFSA beneficiaries an extra 5 kg grain per person per month free of cost. PMGKAY was implemented for eight months (April-November) in 2020-21 and 11 months (May-March) of 2021-22.

NFSA along with PMGKAY has led to a massive jump in grain offtake through the PDS. More importantly, this increase has largely taken place in the poorer states. UP, Bihar and Jharkhand together accounted for 21.6 per cent of national grain offtake in 2012-13, which was pre-NFSA. That stood at 28.6 per cent in 2021-22, higher than their combined 27.8 per cent share of India’s population based on the 2011 Census.

To put the numbers in context, only a handful of states — Kerala, Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh — had well-functioning PDS till the early 2000s. In the late-2000s, Chhattisgarh initiated reforms to curb diversion/leakages by entrusting the running of fair price shops to cooperatives and local bodies (as against private licensees), making timely allocation and supplying grain directly to PDS outlets (bypassing middle-level distribution agencies), and using IT to track dispatches right from procurement centres to points of sale.

Chhattisgarh’s example was emulated by Odisha, followed by Madhya Pradesh and West Bengal — all by 2015-16.

These success stories paid off politically as well. The Bharatiya Janata Party secured successive wins in the 2008 and 2013 Chhattisgarh Assembly elections under Raman Singh, who earned the sobriquet “Chawal Waale Baba (rice monk)”. Mamata Banerjee’s Trinamool Congress was re-elected with an enhanced majority in the 2016 West Bengal polls; ensuring near-universal access to the PDS and rice at Rs 2/kg played a key part in that.

The three poorest states are the latest entrants to the list. UP particularly has seen its grain offtake soar from 9.5 mt to 17.3 mt in the last two years. Out of the 17.3 mt (10.7 mt wheat and 6.6 mt rice) distributed in 2021-22, 7.8 mt comprised free grains under PMGKAY. Most analyses of the BJP’s recent UP elections victory attribute it to the Narendra Modi-Yogi Adityanath “double-engine” government’s focus on not just expanding the reach of the PDS, but also last-mile delivery of grain to the intended beneficiaries.

In sum, the PDS delivered both when and where it mattered. Covid-19 will go down as India’s first major national disaster not to record widespread starvation, unlike the 1943 Bengal or 1966-67 Bihar famines. People in the poorest states got something to eat amid massive job and income losses. The PDS, indeed, turned out to be the only effective social safety net during the pandemic. Some states went beyond rice and wheat. Kerala leveraged its PDS network to supply free food kits to all ration card holders through the 2020 lockdown till around August 2021. These monthly kits — containing items (from coconut oil, pulses, sugar and salt to tea, coriander, turmeric, chilli powder and soap) over and above regular PDS grain — again helped the Pinarayi Vijayan-led Left Democratic Front win a fresh term in the April 2021 state polls.

But that road to success is today hitting a speed bump, which may also create political challenges ahead of the 2024 national elections. The expansion of the PDS, especially post-NFSA, was underwritten by the superabundance of rice and wheat in government granaries. Those overflowing godowns could soon be history. Official wheat procurement is likely to halve this time from last year’s record 43.3 mt, because of a poor crop singed by the abnormal spike in March temperatures. Rice stocks are far more comfortable, though the precarious supply situation in fertilisers raises questions about the prospects for the coming kharif season.

Looking ahead, the Food Corporation of India’s stocks can probably sustain the pre-2020-21 annual offtake levels of 60-65 mt – enough for NFSA, but certainly not schemes such as PMGKAY. The golden chapter of the PDS — including delivering votes to ruling parties — was scripted in an environment of low global commodity prices and surplus domestic foodgrain production. That party is over, even as food inflation is back. The PDS was originally meant to protect ordinary people from extraordinary price rises. Whether it can do that at a time of renewed global inflation remains to be seen.

Written by Harish Damodaran , Samridhi Agarwal

Source: Indian Express, 27/04/22

Graphics: Ritesh Kumar

Graphics: Ritesh Kumar